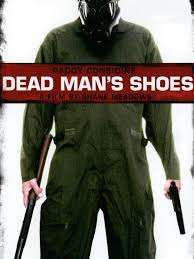

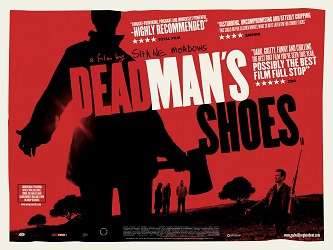

In the canon of British cinema, Dead Man’s Shoes stands out as a raw, unflinching portrayal of vengeance, brotherhood, and the psychological scars of violence. Directed by Shane Meadows and co-written with lead actor Paddy Considine, the 2004 film is a low-budget masterpiece that fuses social realism with psychological horror. It is by turns brutal, touching, and deeply disturbing—a revenge thriller that rejects Hollywood slickness in favor of emotional authenticity.

This is not just a story of retribution; it is a character study of a man unraveling, and of a society that fails its most vulnerable.

Plot Summary: The Return of a Soldier

The film opens with Richard (Paddy Considine), an intense, haunted ex-soldier, returning to his grim, post-industrial hometown in the English Midlands. With him is his mentally disabled younger brother, Anthony (Toby Kebbell). As they roam the desolate streets and fields, Richard delivers cryptic monologues and begins plotting vengeance against a group of local drug-dealers and petty criminals who abused Anthony while Richard was away in the military.

One by one, the gang members begin to fall victim to Richard’s increasingly violent campaign. At first, they are confused—then terrified—as Richard psychologically and physically dismantles them. It becomes clear that he is not just seeking revenge; he is exorcising deep, unresolved guilt and trauma.

As the story unfolds, we begin to question what we’re seeing. Are things really as they seem? What happened to Anthony? The film’s shocking third act recontextualizes everything that came before it, forcing viewers to reassess Richard’s actions and sanity.

Performance: Paddy Considine’s Career-Defining Role

Paddy Considine, who also co-wrote the film, delivers one of the most chilling and affecting performances in British cinema. His portrayal of Richard is simultaneously empathetic and terrifying. He is a man broken by war and personal failure, driven by rage yet rooted in deep sorrow and love for his brother.

Considine brings an unpredictable energy to the role. At one moment, he is calm and thoughtful; the next, he’s a coiled spring of menace. His interactions with the gang members range from eerily quiet to explosively violent. He isn’t a traditional action antihero—there’s nothing glamorous about his revenge. It’s raw, messy, and deeply sad.

Toby Kebbell is equally powerful in his breakthrough role as Anthony. His portrayal of a mentally disabled young man is nuanced and sensitive, never veering into caricature. Through flashbacks, we see the innocence and vulnerability that made Anthony a target—and we understand the depth of Richard’s guilt and fury.

The gang members—played by a mix of professional and non-professional actors—feel authentic. They’re not supervillains or stylized criminals. They’re pathetic, immature, and dangerously thoughtless—exactly the kind of people who would do irreparable harm without even fully grasping it.

Tone and Direction: A Gritty, Intimate Style

Shane Meadows is known for his working-class realism (This Is England, A Room for Romeo Brass), and Dead Man’s Shoes may be his most intimate and emotionally potent film. Shot on a shoestring budget over three weeks, it has a documentary-like feel. The handheld cinematography, natural lighting, and unscripted dialogue contribute to a haunting sense of realism.

The film avoids conventional thriller tropes. There’s no slick editing or dramatic music cues. Instead, it leans into silence, eerie stillness, and the tension of unspoken emotions. The Midlands setting—with its abandoned buildings, grey skies, and empty streets—becomes a character in itself: bleak, lonely, and full of ghosts.

The soundtrack, a mix of haunting acoustic tracks (by Smog, Calexico, Aphex Twin), perfectly captures the film’s melancholic tone. The music enhances the story without overpowering it, often juxtaposing gentle melodies with brutal imagery.

Themes: Revenge, Guilt, and Mental Illness

At its core, Dead Man’s Shoes is about how people deal with trauma—both inflicted and received. Richard is a soldier not just in the literal sense, but also in the emotional sense: he’s spent his life protecting his brother, and failing at that mission destroyed him.

The revenge plot, while central, is not glorified. In fact, the film slowly dismantles the viewer’s desire for retribution. As Richard’s actions grow more violent and erratic, we begin to question his morality—and his grip on reality.

The film also delves into the cruelty faced by people with disabilities. Anthony’s abuse is portrayed not in exaggerated horror, but in small, painful humiliations—mockery, manipulation, neglect. These moments, shown in flashback, are among the most devastating in the film.

Perhaps the most powerful theme is guilt. Richard is not just punishing the men who hurt his brother—he is punishing himself. His descent into violence is not redemptive; it’s self-destructive.

The Twist: A Heartbreaking Revelation

Without spoiling the ending, Dead Man’s Shoes delivers a twist that changes the entire film. What seemed like a straightforward revenge tale becomes something far more tragic and psychologically complex. This final reveal adds emotional depth and elevates the film from a genre exercise into something closer to a modern-day tragedy.

The final scenes are among the most haunting in British cinema—quiet, devastating, and unforgettable.

Criticisms and Limitations

Some viewers may find the film too bleak or too slow-paced. Its minimalism, while effective, demands patience. It doesn’t offer the catharsis or excitement of a typical revenge thriller, and its lack of exposition may leave some frustrated.

However, these are also the film’s strengths. Dead Man’s Shoes is uncompromising in its vision. It doesn’t try to entertain—it tries to make you feel something real and uncomfortable.

Final Verdict: 9.5/10

Dead Man’s Shoes is a brutal, deeply affecting film that lingers long after the credits roll. Anchored by a ferocious and tragic performance from Paddy Considine and directed with raw sensitivity by Shane Meadows, it redefines the revenge genre as something more human—and more harrowing.

This is not a film about justice. It’s a film about pain, memory, and the ghosts we carry. It’s one of the most powerful British films of the 2000s—and perhaps one of the most emotionally honest portrayals of revenge ever put on screen.