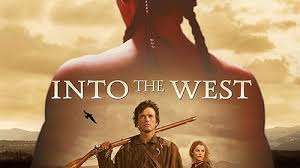

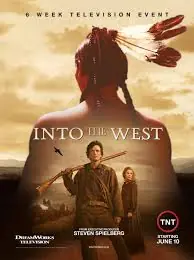

Steven Spielberg’s Into the West (2005) is more than just a television miniseries. It’s a six-part epic that attempts to chronicle the transformation of the American West from untouched land to fractured frontier, through the eyes of both the white settlers and the Native American tribes whose lives were irreparably altered. Ambitious in scale and earnest in message, Into the West offers a powerful, if occasionally uneven, viewing experience—one that aims to present history not as myth, but as a mosaic of clashing truths.

Overview

Originally aired on TNT in 2005, Into the West is produced by DreamWorks Television and executive produced by Steven Spielberg. Each of the six episodes runs about 90 minutes and covers a different period in American history, from the 1820s through the end of the 19th century. The narrative is told in parallel, following two primary families: the white Wheeler family, whose members head West in pursuit of adventure and fortune, and the Lakota Sioux, particularly the lineage of a boy named White Feather, later known as Loved by the Buffalo.

The miniseries features a sprawling cast that includes Keri Russell, Josh Brolin, Skeet Ulrich, Matthew Settle, Zahn McClarnon, Wes Studi, Irene Bedard, Graham Greene, and many others. With a mix of fictional and historical characters, Into the West blurs the line between drama and docudrama, using its characters as vessels to explore the cultural, political, and personal forces that shaped the West.

A Tale of Two Worlds

What makes Into the West compelling is its attempt to present the collision between Native American and settler cultures with nuance and humanity. The dual narrative structure—interweaving the Lakota and Wheeler stories—allows viewers to experience the deep losses and triumphs on both sides. While the settlers are shown braving disease, poverty, and heartbreak, the Lakota are depicted as wise, complex, and increasingly endangered by a culture that refuses to understand them.

The miniseries does not flinch from the brutality of westward expansion. It depicts the systematic displacement of Native peoples, broken treaties, massacres, and the erosion of sacred traditions. Yet, it also portrays the internal conflicts within both communities: the settlers wrestling with morality versus ambition, and the Lakota debating whether to resist or adapt to the encroaching tide.

This duality is personified in characters like Jacob Wheeler (played by Matthew Settle), a blacksmith-turned-explorer whose hunger for the unknown leads him far from home, and Loved by the Buffalo (Simon R. Baker), a visionary caught between the fading past and an uncertain future. Their stories intertwine in unexpected ways, revealing how deeply connected—and ultimately damaged—both worlds become.

Production Value and Cinematic Quality

Visually, Into the West is stunning. The cinematography captures the awe-inspiring landscapes of the American frontier, from vast plains and rugged mountains to barren deserts. The attention to period detail is exceptional—costumes, weapons, transportation, and settlements are all depicted with historical accuracy and artistic care.

The direction, shared across several episodes by Robert Dornhelm, Sergio Mimica-Gezzan, Michael Watkins, and Timothy Van Patten, is consistent and grounded. There’s a quiet reverence in the way scenes unfold, especially when portraying Native ceremonies, settler hardships, or the bloody aftermath of battles. The music, composed by Geoff Zanelli and Hans Zimmer, enhances the emotional resonance without overwhelming the storytelling.

Strong Performances Amid a Massive Cast

Given the enormous ensemble, it’s impressive how many characters leave a lasting impression. Skeet Ulrich delivers a standout performance as Jethro Wheeler, a man haunted by his own ideals and failures. Zahn McClarnon shines in a breakout role as Running Fox, bringing dignity and complexity to a character often forced into impossible choices. Irene Bedard is luminous as Thunder Heart Woman, one of the most fully realized Native characters in the series.

The Native American cast in general is a strength of the production. Spielberg and the creators made a conscious decision to include native actors, dialogue in Lakota and other indigenous languages, and cultural consultants. This commitment shows, especially in scenes involving ceremonies, tribal councils, and spiritual visions. The series treats Native culture not as exotic backdrop, but as a living, breathing force that deserves its own narrative weight.

That said, with so many characters and so much ground to cover, not every arc lands with equal force. Some subplots feel underdeveloped, particularly those involving secondary settlers or historical figures shoehorned into the script. There are moments when the miniseries tries to do too much and ends up glossing over significant emotional beats.

Historical Accuracy vs. Dramatic License

As with many historical dramas, Into the West walks a fine line between fact and fiction. Real-life figures like General Custer, Kit Carson, Red Cloud, and Sitting Bull make appearances, and key events such as the Sand Creek Massacre, the Trail of Tears, and the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad are all depicted.

While the creators strive for authenticity, some critics have noted that the portrayal of certain events can feel sanitized or overly dramatized for effect. For example, Custer is painted in broad strokes, and the complexity of U.S. government policies toward Native tribes is sometimes simplified for narrative clarity. However, these compromises are arguably necessary for storytelling in a format that must entertain as well as educate.

Importantly, the series never veers into glorification. If anything, it is unsparing in its critique of Manifest Destiny and the hypocrisy that fueled it. The white settlers are not presented as heroes, but as flawed human beings swept up in a wave of ambition and ideology. Native resistance is framed not as barbarism, but as an act of survival.

Legacy and Impact

Though Into the West won several technical awards and was praised for its scope and ambition, it has been somewhat forgotten in the broader landscape of prestige television. That’s unfortunate, because few TV productions have attempted to address Native American history on this scale—or with this level of sincerity.

Its most valuable contribution may be its commitment to presenting two parallel truths: the mythic West and the real one. It acknowledges that the story of America’s expansion is not one of clear victories, but of contested land, cultural erasure, and spiritual loss.

In an era where the conversation around indigenous representation in media is gaining momentum, Into the West deserves to be revisited. It’s a bold attempt to reckon with the past—not just the past of the characters onscreen, but the collective past of a nation.

Final Thoughts

Into the West is not flawless, but it is deeply moving and richly realized. It is a miniseries with heart, weight, and a willingness to confront painful truths. It asks hard questions: What was gained? What was lost? And at what cost?

For those willing to invest the time, it offers a haunting, human portrait of a country in the making—and the many lives changed, shattered, or erased along the way.

Rating: 8.5/10